Can the Sage Save China?

Beijing is hoping a return to Confucian values will help quell growing dissent, and inspire new loyalty.

By Benjamin Robertson and Melinda Liu

Newsweek International

March 20, 2006 issue - China's official buzzword these days is "harmony." Whether the audience is Chinese or foreign, rich or poor, Beijing's leaders are spreading the message: can't we all just get along? After becoming president in 2003, Hu Jintao made the pursuit of a "harmonious society" his personal mantra. Last week Prime Minister Wen Jiabao echoed the same sentiment before the current session of China's Parliament; the gathering has focused on improving health care and education for the rural poor, who have increasingly been left behind by China's economic boom. Foreign Minister Li Zhaoxing has got into the act, too, trying to market the message abroad. "The Chinese nation has always pursued a life in harmony with other nations, despite differences," he said recently. What few of China's top leaders acknowledge out loud, however, is that Hu's slogan actually harks back to a famous—and ancient—Chinese personality: Confucius.

After about a century in the political wilderness, the Great Sage, who is believed to have lived from 551 to 479 B.C., is in vogue again in China. Confucian values—unity, morality, respect for authority, the importance of hierarchical relationships—are being touted by Beijing's communist leaders as never before. Four decades ago, during the Cultural Revolution, Confucianism was vilified as a pillar of feudal despotism. But last September, the government's birthday bash for Confucius was the most lavish since 1949, replete with costumed pageantry and tens of thousands of participants. Among them were 100 scholars who discussed how Confucianism could serve as the "moral foundation" for the country. Hu himself has not publicly declared that Confucianism should fill China's current ideological void. In February 2005, however, he evoked the sage's name—"Confucius said, 'Harmony is something to be cherished'"—in a speech to senior cadres on how social cohesion would help stave off "economic stagnation and social upheaval."

The domestic reasons for Hu's campaign are self-evident. Market reforms, a white-hot economy and a culture obsessed with getting ahead have unleashed envy and discontent among China's 1.3 billion people. There is simmering social unrest, especially in the countryside, where residents are unhappy about corruption, land confiscations and, perhaps most important, stagnant incomes. In a 2005 survey, nearly three quarters of respondents said "money" was what they desired most. Beijing University professor Kong Qingdong, who claims to be a descendant of the ancient sage, ticks off the flash points: "The rich-poor gap, job layoffs, more and more petitioners publicly airing grievances, deteriorating social security and other contradictions."

Clearly the Communist Party needs a new ideology to heal these wounds. Marxism no longer inspires, and the "gospel of greed" that replaced collectivism and has helped power economic growth is morphing into what some experts say is a virulent form of crony capitalism. That leaves only the glue of nationalism to hold China together. But it's a double-edged sword. Indeed, Chinese leaders were deeply rattled by eruptions of violent anti-Japanese and anti-U.S. riots over the past half decade, which helped put bilateral relations with Tokyo into the deep freeze and ties with Washington into a wary holding pattern. Confucianism, on the other hand, is not only quintessentially Chinese, but also pacifist and nonthreatening to other nations. "It stresses datong, which proposes that all the world's people should become one big family," says Kong, who began advocating a "harmonious society" years ago.

Scholar Kang Xiaoguang, the country's top proponent of Confucian education, thinks Confucian values are similarly the answer to China's new go-go culture. "Chinese society today is at its worst ever," he says. "The problem is that there are no moral standards to regulate how people treat each other, their business partners, their friends and families. Relationships are ambiguous and we have no way of judging what makes a happy life."

Once a social-policy adviser to the then Prime Minister Zhu Rongji, Kang hopes to see Confucian education become mandatory for all schoolchildren. Things haven't gotten that far yet, but the Education Ministry has given the green light to proposals by Kang and his colleagues for schools to adopt 30-session courses in traditional Confucian culture. More than 5 million primary-school students now study Confucius in the classroom. What's more, 18 major universities hold courses in Confucian philosophy, or host Confucius research institutes. At the Confucius Research Academy of China's People's University, special commemorative activities held the last two years feature children reading aloud from The Analects—a compilation of the philosopher's basic teachings. "We've increased Confucian learning greatly compared with 10 years ago, when few people dared to mention Confucian principles," says academy Dean Zhang Liwen.

For their part, Hu & Co. are clearly hoping a Confucian revival can help dampen grass-roots challenges to government authority, which are mounting so fast that local officials are being told their promotion prospects depend partly on whether they can keep a lid on unrest. Confucianism not only prizes social harmony, but dictates that citizens should obey the emperor if he, in turn, wields the so-called mandate of heaven in a moral way. "The government has found that a Leninist method of government is too rigid, while democratic government has an anarchic quality that is too destabilizing," says Richard Baum, director of the UCLA Center for Chinese Studies. "The Confucian idea of a 'mandate of heaven,' where the emperor ruled with a virtually absolute mandate, provided he took care of the people, is very close to the modern-day notion of a benevolent despotism."

There is rich irony in the rehabilitation of Confucius. During Mao's day, Confucianism was reviled for its "father knows best" philosophy. The Great Helmsman even charged that a bizarre assassination plot by his handpicked successor Lin Biao was intellectually inspired by Confucian thought. "During the 'anti-Lin and anti-Confucius' political campaigns, the Great Sage's philosophy and personal integrity were thoroughly trashed," says Sinologist Minxin Pei of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace (following story).

For some of the same reasons that Confucius was a dirty word in Mao's day, not everyone welcomes his return. Confucian values, for example, often show a gender bias favoring males. Critic Hu Xingdou, a lecturer at the Beijing Institute of Technology, also complains that by emphasizing moral conduct in political life, China's leaders are avoiding tackling the systematic origins of corruption and poor governance that deeply afflict the nation. "You cannot completely copy a traditional belief system in the modern era," he says. "Confucius places a priority on how people should behave, asking them to suppress desire and adhere to a high level of moral etiquette. This is unrealistic." U.S. Sinologist Baum agrees that the current Confucius craze "is a weak substitute for real institutional reform... Mao always used to stress that people could change their consciousness through self-criticism—and now [authorities] are doing it again by saying the solution to corruption is to educate moral people. It's a coat of paint." China's retrogression also seems out of step with other Confucian-influenced societies; Singaporeans no longer tout "Asia values," while Confucius-bashing became fashionable in South Korea as early as 1999, with the publication of a book titled "The Country Lives If Confucius Dies."

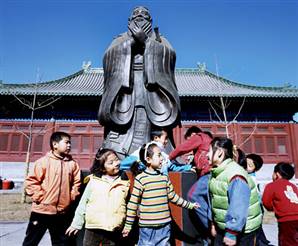

Such criticisms don't deter Confucius' most ardent advocates. A five-meter-tall Confucius statue stands in the courtyard of Beijing's Fuxue Primary School. Founded in 1358 as a temple school for students of ancient scriptures, Fuxue became a showcase primary school after it brought Confucius into the classroom in 2003. Head instructor Wang Xiaochun says one couple enrolled their son after they were horrified to discover he couldn't recognize a statue of the famous sage. In a small side room, a museum details Confucius' life. A glass engraving of the educator, portrayed with a stereotypically wispy beard, greets visitors as they step over the raised doorway.

Kang Xiaoguang has grand ideas for expanding the philosopher's reach. Already, he says, the debate within the government is not whether to resurrect Master Kong, as Confucius was known, but on which pedestal to enshrine his teachings—as part of the education system, as a political ideology or as a national religion. Waving his cigarette around like a magician's wand, the chain-smoking scholar, who works for the China International Research Center, conjures up images of the Great Sage's ethos making a great leap overseas as well. "I don't expect other countries to accept Confucius, but if China and the world uses Confucian theory as a basis for international relations, it would benefit everyone, as moral rightness would overcome self-interest." He calls this part of "the rise of Chinese cultural hegemony."

That phrase doesn't sit well with officials of the Foreign Ministry, who spend much of their time trying to avoid any connection with hegemony of any kind. Indeed, the question of whether China can sacrifice its narrow self-interests for the sake of the international good is a hot topic among analysts watching China's rise. —Last September, U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick made an important policy speech that asked whether Beijing was ready to play the role of a "responsible stakeholder" in the international community. He warned China about the dangers of a "mercantilist" strategy toward nailing down global energy resources, and of forging intimate ties to regimes of ill repute.

Partly to assuage such concerns, over the past two years China's Foreign and Education ministries have been quietly establishing a worldwide series of Chinese cultural centers aimed at promoting Chinese-language instruction and Beijing's image abroad, much the same way Goethe Institutes do for Germany, or British Councils for the United Kingdom. A $10 billion program envisages the creation of 100 so-called Confucius Institutes worldwide by 2010. The first was built in South Korea, and others have opened in the United States, Canada, Germany and Kenya. Catering to a growing international demand for Chinese-language study, the government hopes within a decade to have 200 schools promoting and teaching Chinese, arts, music and culture, including the legacy of Confucius.

The avuncular image of Confucius could help temper overseas perceptions of China as a rapacious juggernaut. Instead, says Baum, China will present a "softer Confucian face rather than the hard-line communist face." Hu's regime clearly hopes that the historical appeal and benign trappings of the ancient sage will help Beijing win friends and influence people overseas. But even if Confucius sells well abroad, the bigger question is whether his comeback will have the desired effect back home.

With bureau reports

No comments:

Post a Comment